The Sinking of the

SS PORTLAND

The loss of the SS PORTLAND in the November gale of 1898 remains one of Cape Cod's most notorious shipwrecks. A combination of bad weather and bad luck lead to the loss of an estimated 192 lives.

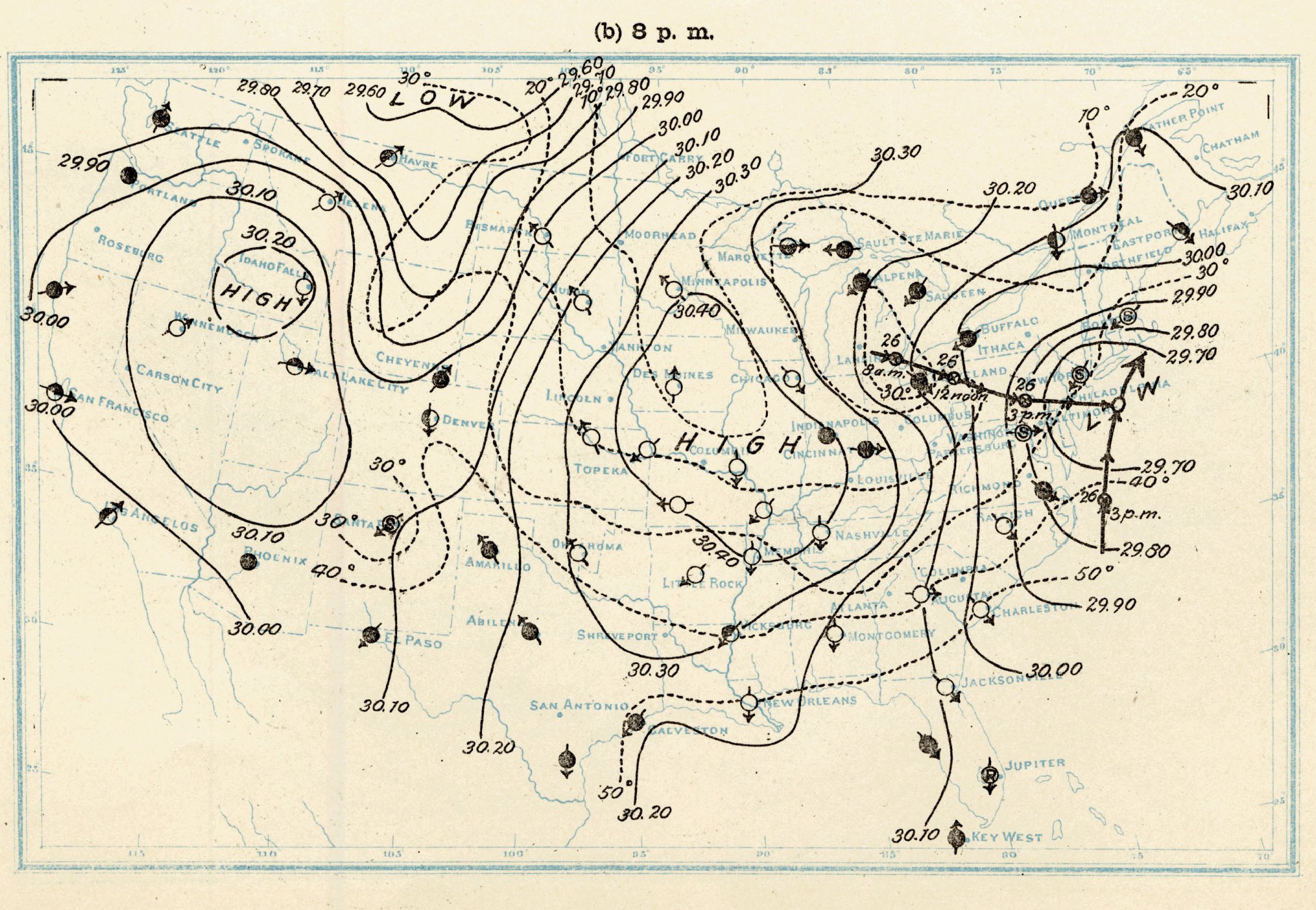

19th Century Weather Forecasting

New England had battled with devastating storms in the 17th, 18th, and 19th centuries, but none yet were as destructive or as deadly as the Portland Gale.

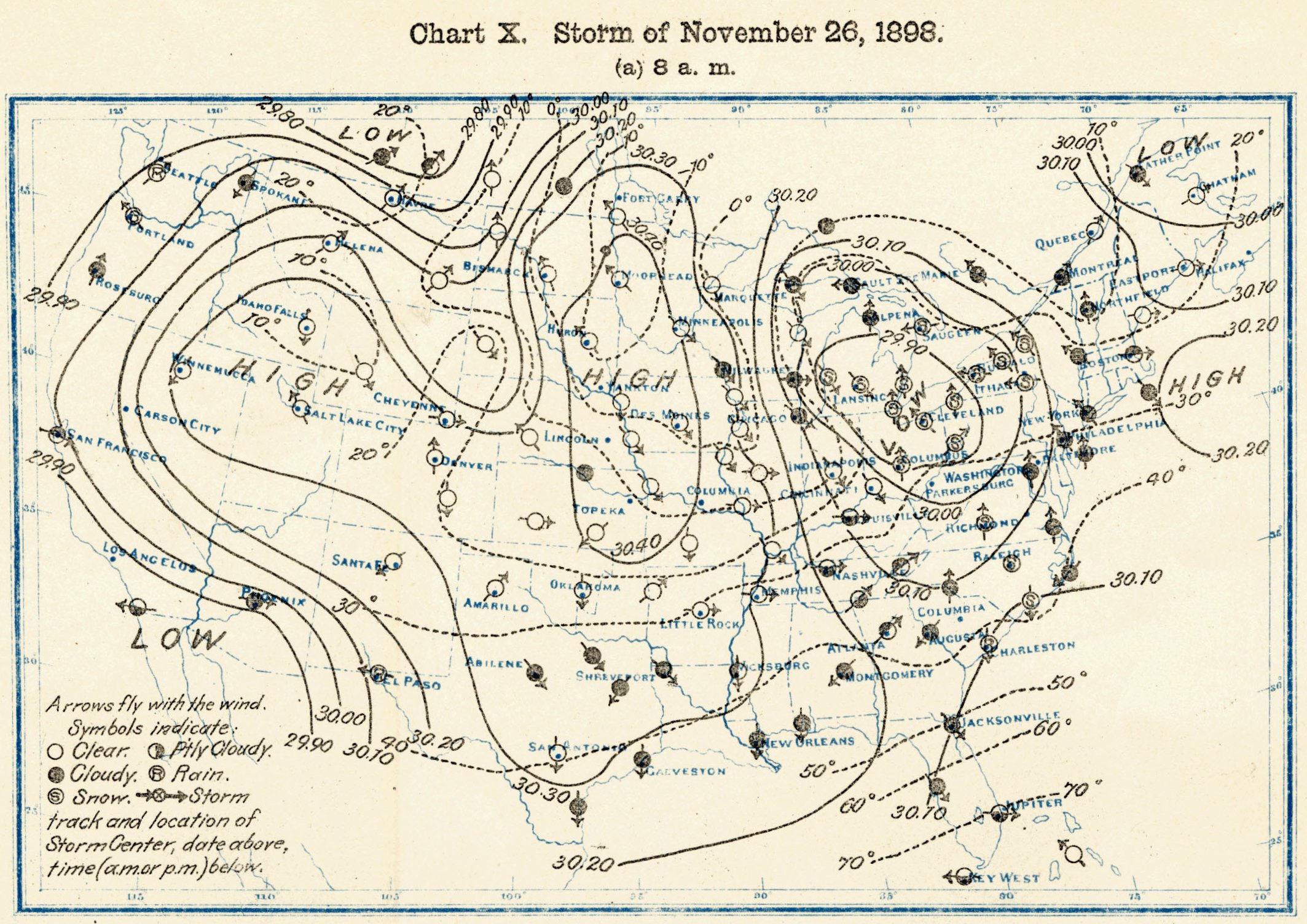

In the late 19th century, weather forecasting was limited.

Forecasts were issued from the U.S. Weather Bureau headquarters in Washington, DC, to regional offices around the country, who then relayed the information to local newspapers.

While the Weather Bureau warned of the possibility of a storm in New England slated to hit the weekend after Thanksgiving in 1898, the magnitude and timing of it were not known until it was too late.

Buffalo Evening News

The 19th Century's Perfect Storm

November 26, 1898: 12:00 pm, Saturday

The weather in Boston, two days after Thanksgiving, was fair, with cold and brisk winds. By noon, the forecast changed drastically and quickly, calling for high winds and seas, with a snow advisory. This created especially dangerous conditions for mariners.

The cause was the cataclysmic merging of two low pressure systems - a cyclone from the Gulf of Mexico, and a large storm system from the Great Lakes.

November 27, 1898: 12:00 am, Sunday

By midnight, temperatures plummeted to below 0°F and 40 inches of snow fell. Hurricane force winds and devastating tidal surges caused severe damage to the shorelines, coastal villages, and vessels of southern New England.

November 28, 1898: 10:00 am, Monday

After 36 hours, coastal New England awoke to widespread damage. The storm blew away or washed away homes along the coast. Shipwrecks and debris littered the coastline from Cape Cod to Portland, Maine. Telegraph and telephone lines were down, railroad tracks were washed into the sea. The storm even changed the shape of some coastlines permanently.

In Provincetown alone, 30 vessels were damaged or sunk. Several whaling wharves and many buildings were destroyed.

The most tragic loss was the SS PORTLAND, which went down with all hands and gave the storm its name.

Fall River Daily Evening News

The Steamship Portland

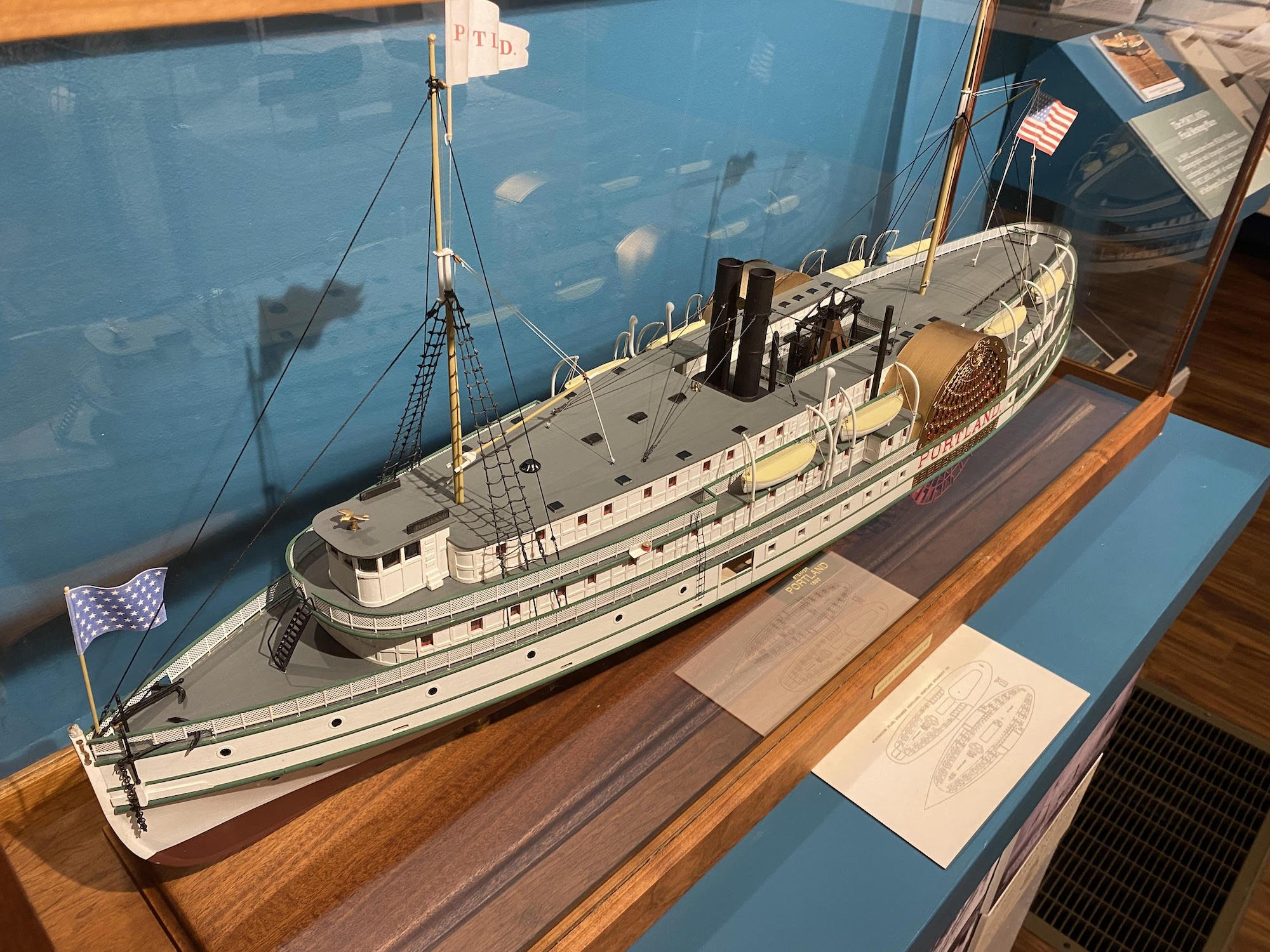

The Steamship PORTLAND

The TITANIC of New England

Built in 1889, the sidewheel steamship PORTLAND was a packet ship. She transported people and goods between Portland, Maine, and Boston, Massachusetts for the Portland Steam Packet Company. She could carry up to 700 passengers per trip, with a crew of 63, but had only 16 lifeboats and 80 life vests.

She was quite a luxurious vessel: during the 8 to 9 hour overnight passage between Portland and Boston, passengers traveled in style. Her 167 staterooms were paneled in cherry, and featured richly carved mahogany furniture, upholstered in decadent wine-colored velvet. Additionally, she featured 514 pine berths in a variety of room sizes. The floors were covered in miles of plush carpeting.

PORTLAND STATISTICS

Commissioned in May 1889 by the Portland Steam Packet Co.

Built and launched in October, 1889, by the New England Shipbuilding Co. of Bath, Maine

281 feet long, 42 feet wide, with wooden hull construction

Fueled by two coal-fired iron boilers, made by the Bath (Maine) Iron Works

Powered by a single cylinder, upright "walking beam" steam engine that turned two paddle wheels with 35' diameter and 8' width

Leslie’s Weekly

The PORTLAND's Last Voyage

November 26, 1898: 7:00 PM, Saturday

The PORTLAND left her wharf in Boston headed to Portland loaded with freight and passengers headed home after the Thanksgiving holiday. While the Captain was warned of impending bad weather, he was not prepared for or not aware of the severity and intensity of the gale. Perhaps he hoped to outrun the storm, which was working its way up the East Coast.

Within hours of departure, conditions at sea had become dire. Hurricane force winds gusted northwards up to 70 mph, with waves reaching 30 feet. Sidewheel steamers, with their long, shallow hulls were incredibly vulnerable in the open seas, and these waves quickly overpowered the PORTLAND, damaging her superstructure and forcing her many miles off her course.

November 27, 1898: Sunday

While the PORTLAND's exact reason for sinking is unknown, it is believed that she finally sank after the thunderous seas washed over her decks. The average time of the watches worn by recovered bodies read 9:15. It is unclear, however, if this indicates the ship was lost at 9:15 PM Saturday, or at 9:15 AM Sunday.

About 192 passengers and crew perished that night. There were no survivors. Bodies and debris washed ashore on Cape Cod beaches for months. With no survivors, the experience of the passengers and the crew during the sinking is unknown, but it could only have been a terrifying ordeal. The sea, unforgiving and surging, would have tossed and rolled the paddlewheel steamer about violently. Roaring winds and freezing weather would have turned this terrible voyage into a living nightmare.

A Model Maker's Insights

Long time docent and museum board member Dr. Keith Richards generously loaned his personal model of the PORTLAND for our exhibit. “I started building ship models about the same time I moved to Cape Cod,” he explained. “I started with simple models built from kits and gradually worked up to more complicated kits as I became more experienced. I mostly chose to build models of boats with interesting stories. I was completely self taught. About twenty years ago I moved on to building models from scratch. Just before I did that I built the model of the Portland, one of the two most complicated kit models I ever attempted.”

Building a 3D replica of the doomed vessel gave Dr. Richards a unique perspective photographs and paintings of the ship can only go so far in showing: “I displayed the model on a shelf above my computer printer. The shelf was high enough so that the paddle wheels were about at eye level. This was not as optimal a viewing angle as is present in the Museum’s exhibit, but it was where I had the space. Had the ship’s owner had a model mounted this high, however, he would have never felt right about sending it to sail on the open ocean in a storm like this.”

While sidewheel steamers were relatively safe vessels on lakes, rivers, and the sea, the bottom of these ships were very wide and flat, with a shallow draft. A freak storm like the gale of 1898 created uniquely dangerous circumstances for a sidewheel steamer.

Dr. Richard explained “Think of the way it might roll in big ocean swells. Then think about the paddle wheels, both connected to the same drive shaft with no differential to allow them to move independently from each other. The wheel on the down side would be buried in the water and under great strain. The wheel on the high side might be completely out of the water and freewheeling. The forces on the drive mechanism would be terrible, and there would be complete loss of steering ability.”

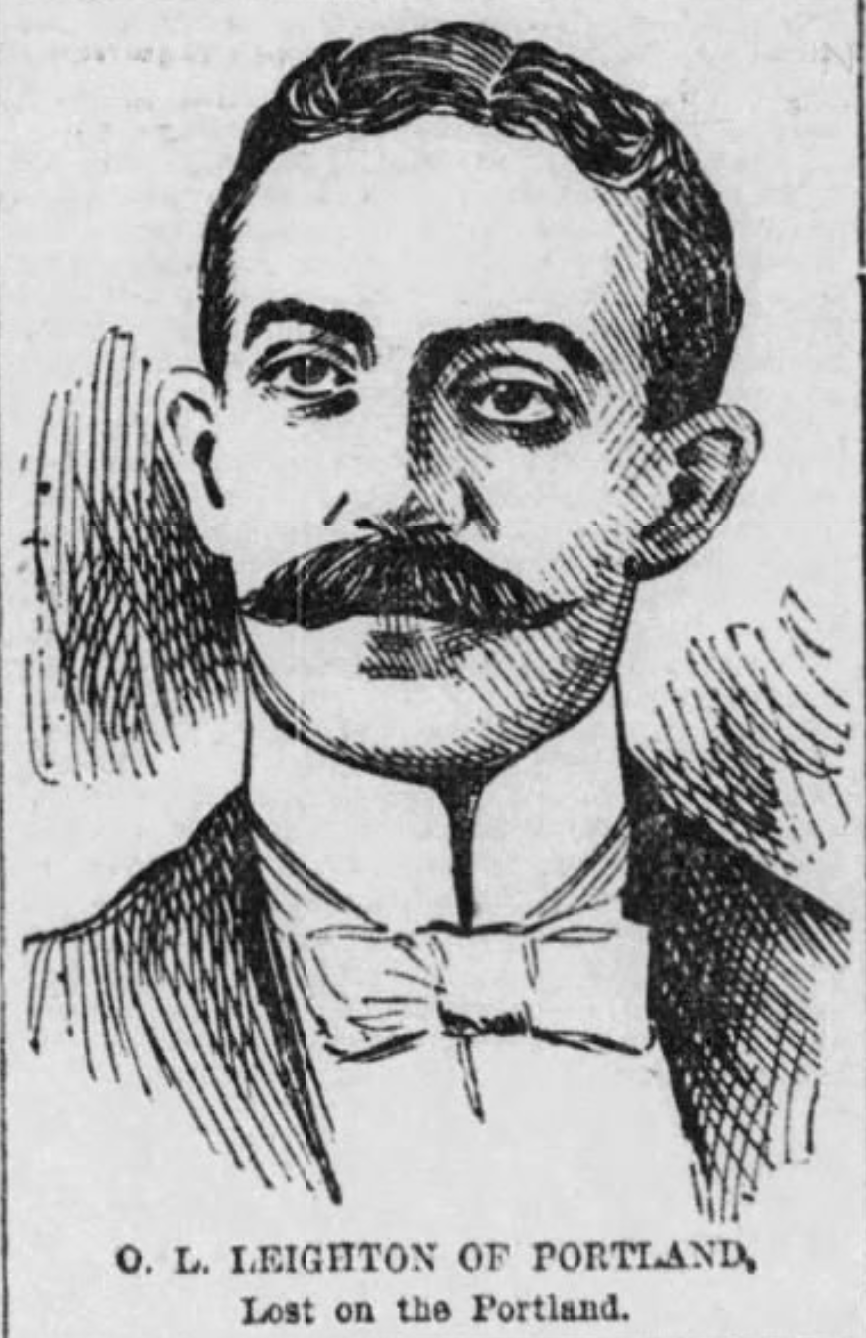

People on the PORTLAND

Most of the passengers and crew aboard the PORTLAND were from Maine. Many were returning home after celebrating Thanksgiving with friends and family in and around Boston. Teachers, artists, businessmen, prominent attorneys, and children with their parents boarded the steamship with no idea what would be in store for them. A family of four, including two young children, only recently returned from the parents’ native Denmark, were among them.

The PORTLAND’s crew was made up of veteran seamen and employees of the Portland Steam Packet Company. Many were Black, and members of a thriving African American community in Portland.

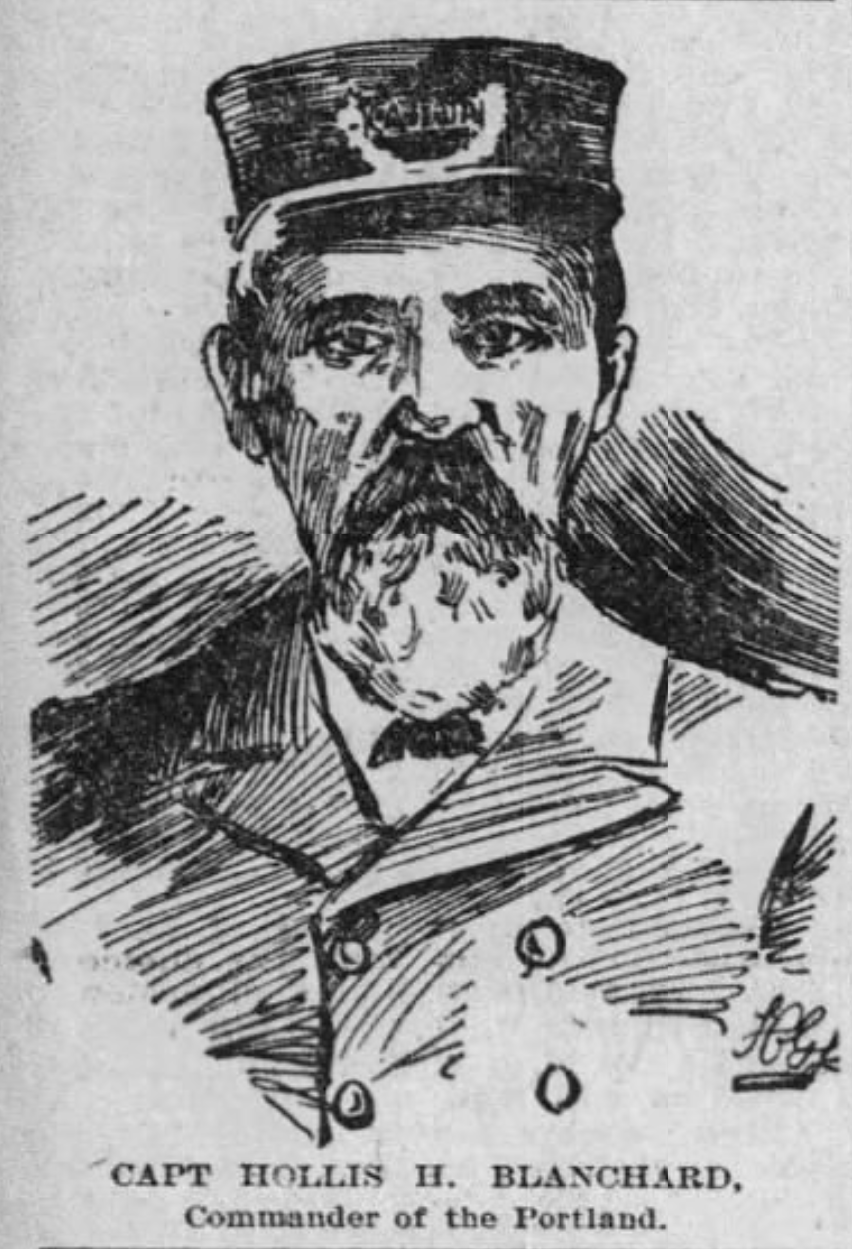

Captain Hollis Blanchard was an experienced seaman and a long time employee of the Portland Steam Packet Company. The question of why he chose to leave port on November 26 remains a mystery.

After the sinking, loved ones provided photographs and sketches in hopes a body might be identified for proper burial. These illustrations were published in local papers, giving us a glimpse of those lost in the disaster.

The Boston Globe

A National Tragedy

Only a few hours after the sinking, debris from the ship began to wash up on the shores of Cape Cod. Surfman John J. Johnson of the Peaked Hill Bars Life-Saving Station remembered: “I was bound west toward the station, when I found the first thing that landed from the steamer. It was a life belt… At 7:45 that evening I found the next seen wreckage, a creamery can, forty quart, I guess. It was right below our station, and nine or ten more of them, all empty and stoppered tightly came on there closely together.”

More sobering were the bodies that began to come to shore, the first - a Black man wearing a life belt, a member of the PORTLAND’s crew - discovered early Monday morning. Most of the PORTLAND passengers' bodies were never found, carried away by ocean currents or entombed within the wreck of the ship.

The sinking of the PORTLAND made national headlines. Desperate family members descended on the Cape to identify bodies, or in hopes more would wash ashore. For some time after the disaster, it was unclear exactly who had been on board and who had chosen to sail another day. The only passenger list went down with the ship. After the disaster, the Portland Steam Packet Company began to keep two lists - one on board, and one safely on land in case of another disaster. Other passenger lines began to adopt this same practice.

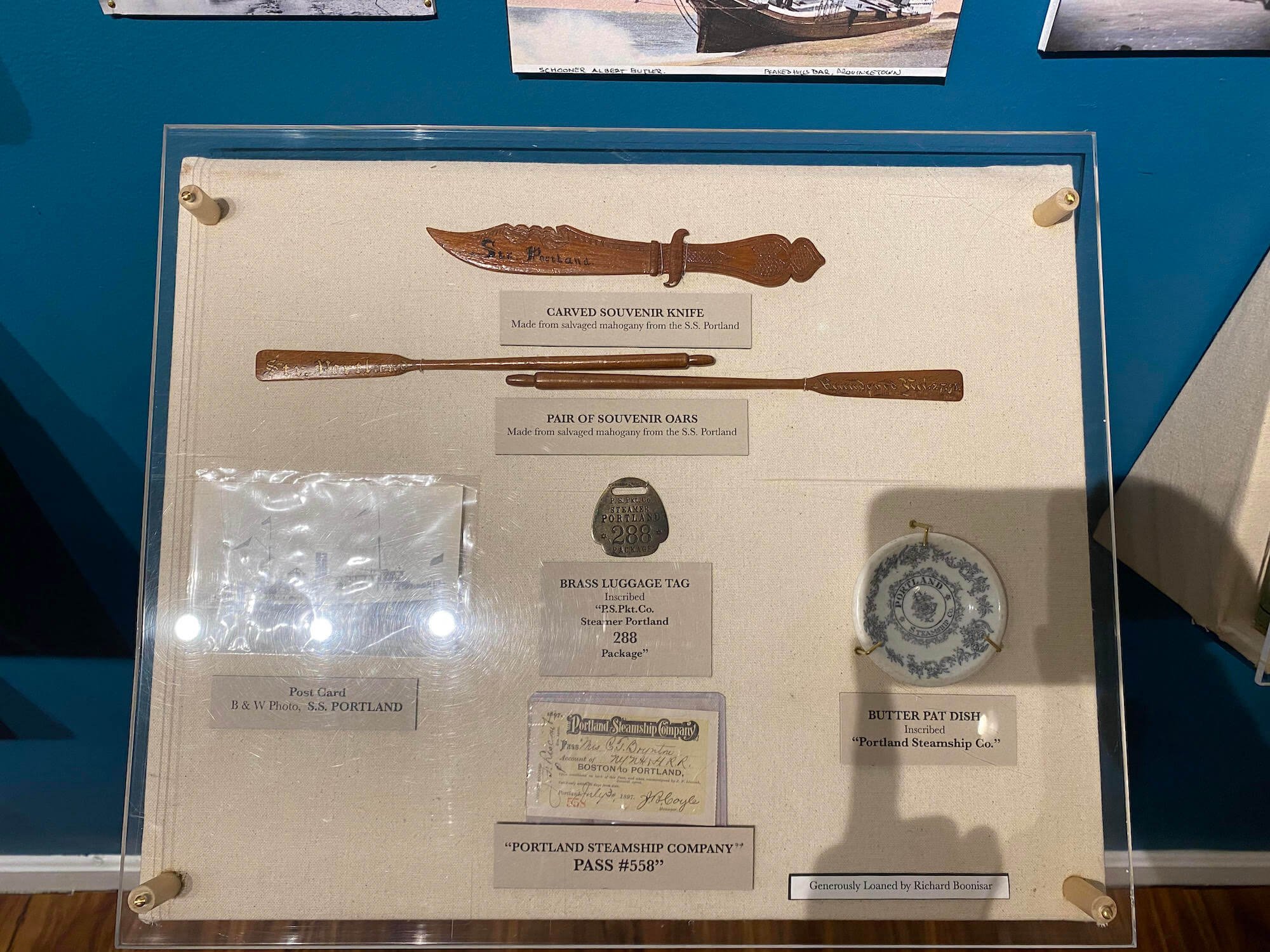

These artifacts - generously loaned to CCMM by Richard Boonisar - are a small representation of the artifacts recovered after the wreck. The books are in such good condition after the sinking because they were in a leather backpack.

National Archives and Records Administration

Real Lives Lost

The Portland Gale remains New England’s most disastrous maritime tragedy. In all, the storm resulted in more than 500 deaths, and the loss of 150 vessels. Most of those killed in the storm were the approximately 129 passengers and 63 crew members on board the PORTLAND.

Many of the crew members were the sole breadwinner of their families. The women and children left behind after their deaths had to deal not only with grief, but desperate financial situations. In a few instances, mothers were forced to give up their children for adoption following the death of their husbands to keep them from total poverty.

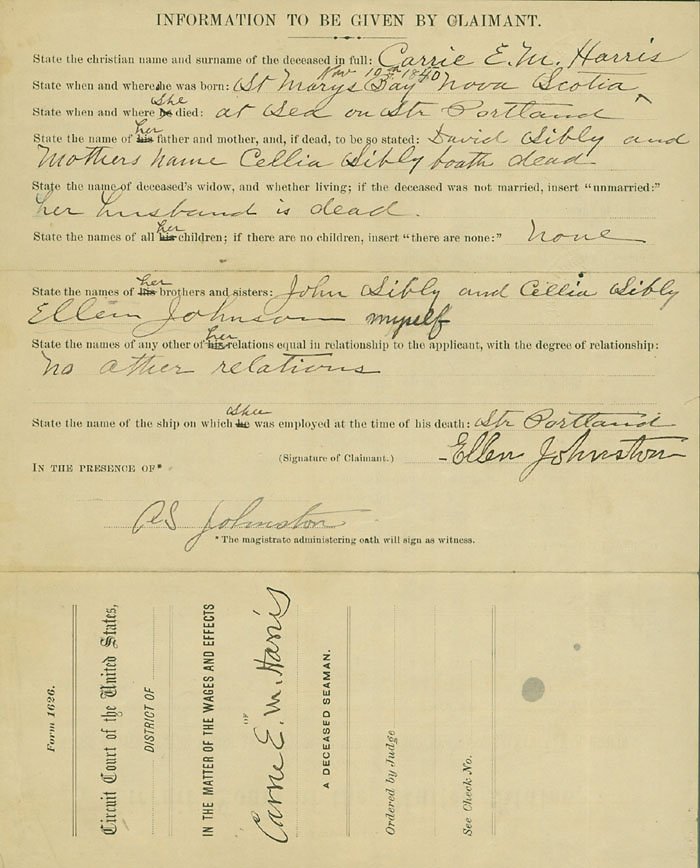

Interestingly, modern historians can reconstruct the crew list on the PORTLAND’s final voyage from the claims their family members made with the shipping commissioner for their final paychecks. Claims like the two Ellen Johnston of Portland, Maine filed for her husband, Arthur, the ship’s saloon watchman, and her sister, Mrs. Carrie E.M. Harris, head stewardess, tell us not only the names of the people lost, but also their family connections, home address, and other genealogical information.

Small communities were especially hard-hit. Of the 63 crew members lost, 19 were from the African American community of Portland, Maine. Their loss fragmented the community, and eventually led to the closure of the city's Abyssinian Meeting House, an important cultural center. There are current efforts underway to restore this Meeting House as a historic building dedicated to the quest for personal freedom, civil rights, and equal opportunity for all.

Boston Globe

The PORTLAND’s Final Resting Place

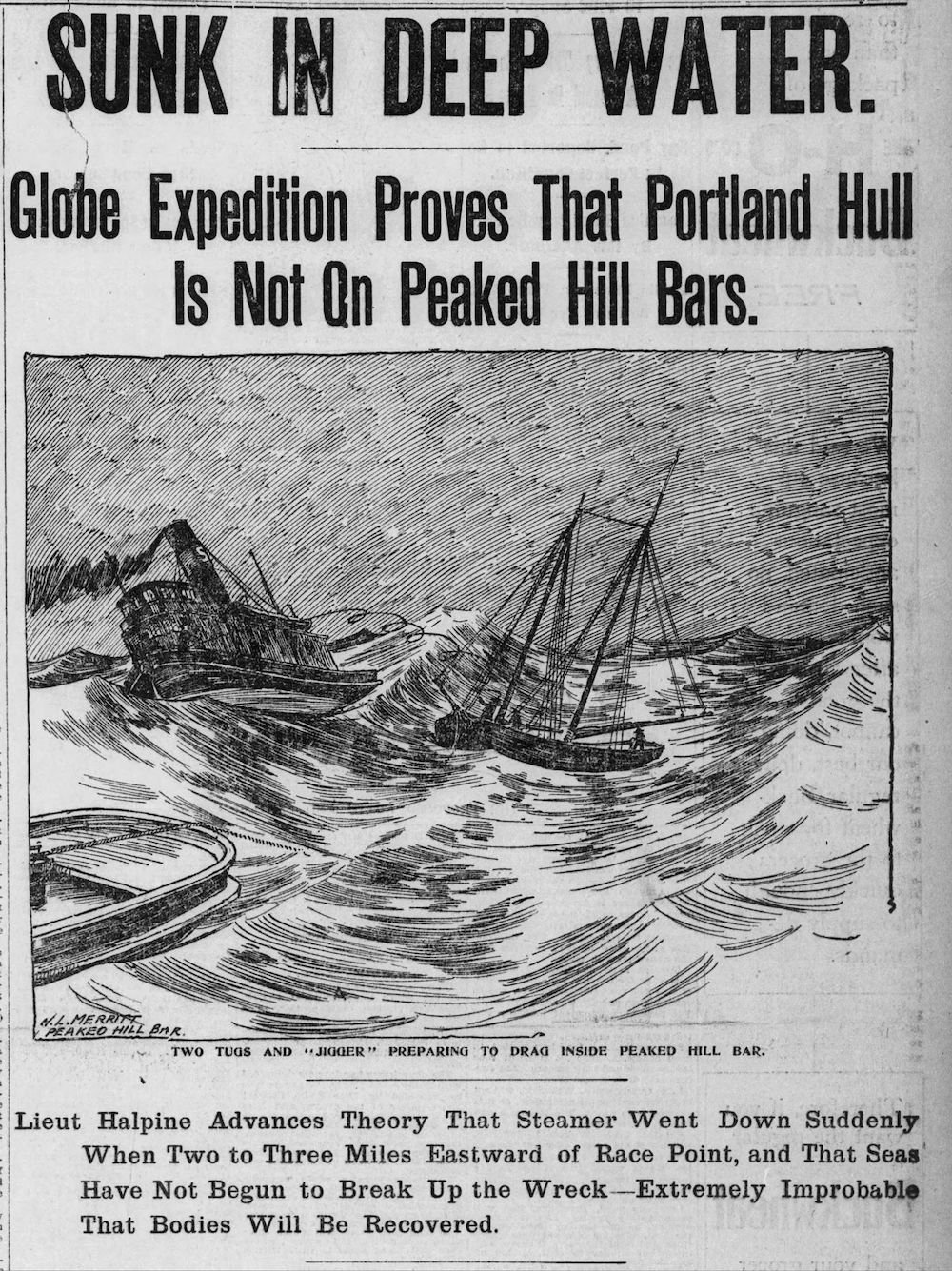

For decades, the location of the PORTLAND’s wreck site remained a mystery. Shortly after the sinking, several investigations including one financed by the Boston Globe attempted to find the wreck. For years after the storm, fishing vessels would bring in debris from the PORTLAND, some only nine miles off Cape Cod’s Highland Light, while others further into Massachusetts Bay.

The wreck itself was first discovered in 1989. In 2002, researchers from NOAA (National Oceanographic and Atmospheric Administration) confirmed the location of the remains of the PORTLAND in 300 feet of water at the southern part of Stellwagen Bank, just miles off Provincetown.

The development of this exhibit was supported by a "Sustaining the Humanities through the American Rescue Plan (SHARP)" grant, made possible through funding provided to the National Endowment for the Humanities (NEH) by the American Rescue Plan, and awarded through NEH's state affiliate, Mass Humanities.